Why do cute things make us feel so good?

Sylvanian Families, squiggly mirrors and emojis: we look at what cute means today

Sylvanian Families, squiggly mirrors and emojis: we look at what cute means today

In the music video for 2023’s ‘Perfect Picture’, Hannah Diamond wears her bubblegum hair in pigtails, a coquette-like bow on her shoulder, another on her hip. A vision in pink sporting an Angelina Ballerina-meets-Carrie Bradshaw tutu, the look draws on girly signifiers and gloriously services her distinctive brand of pop. It’s unsurprising then, that Diamond was so crucial to the genesis of a new exhibition about all things cute. “I was listening to her talk about her practice, and the way she was talking about hyperpop and PC Music – also her experiences as a woman, leaning into maximal femininity and embracing cuteness – I found incredibly powerful,” says Claire Catterall, senior curator at Somerset House, where a new exhibition about the ‘irresistible rise of cuteness’ opens this week. “She was the first thing that made me sit up and take notice.”

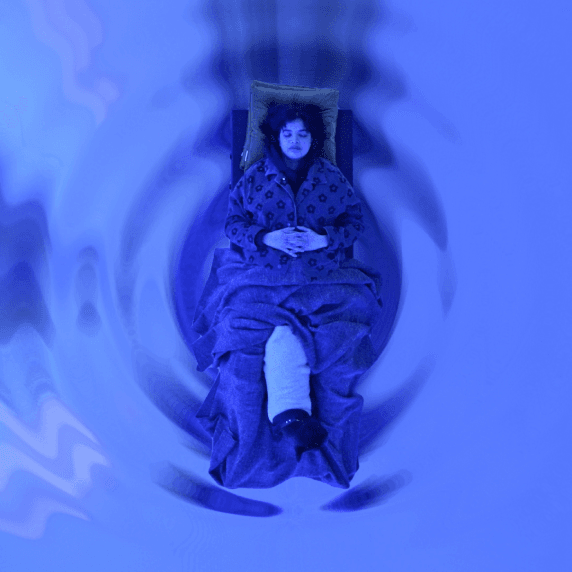

CUTE zooms in on art, fashion, social media, toys and music – including an immersive installation inspired by a girl’s sleepover created by Diamond – to examine what the term means today. “It’s one of the most dominant aesthetics of our contemporary world, completely saturating our lives,” Catterall says of cute’s ascent. “It’s a new language. 30 years ago, cute was only found in toys, decorative knick knacks and greetings cards – now even information graphics, usually so boring, have become cute.”

“Obviously cute’s been used before, with Riot Grrrl in the ‘90s,” she continues, referencing the feminist subculture that gave us Bikini Kill and Sleater-Kinney, “but they used it ironically, expressing ideas around the ridiculousness of femininity. Hannah’s doing almost the opposite, saying I can be vulnerable and wear pink, and still be a strong woman.” Indeed, while cute has since inserted itself into the mainstream, it didn’t happen overnight: in an interview in 2023, Diamond, whose first single ‘Pink and Blue’ landed in 2013, alluded to culture’s changing appetite for cute, stating, “I honestly think the world wasn’t ready for that cute personality and world I was creating when I first started out.”

Beyond infiltrating our wardrobes and Spotify streams, emblems of cute today underscore our home interiors (squiggly mirrors? Pretty cute coded), holidays, and the way we converse: the emoji has long been king, while memes are practically a sixth love language. And yet, what exactly is cute? Catterall says that “cuteness is unwieldy because it encompasses so many different things. It’s such an ambiguous term.” Maybe, but moreover, why do cute things make us feel good, and why are we so willing to let them dominate our lives? How did the @sylvaniandrama TikTok account reach 2 million followers, and when did @miffydances find my Instagram Explore page? Why am I, genuinely, so enthralled by a cartoon rabbit dancing to Fleetwood Mac and Sophie Ellis-Bextor?

“Cute things have mood-lifting effects, activating the brain’s reward system and releasing dopamine, which creates a sense of enjoyment and pleasure,” Laura Noir, a clinical psychologist based in Adelaide, tells woo. “Cuteness triggers feelings of affection and joy, activating nurturing instincts that promote social bonding and cooperation. And this attraction isn’t just a quirk, it has an evolutionary advantage: the pleasure response linked to cuteness encourages caregiving behaviour, which when activated gives us a sense of responsibility, making us feel connected to others.”

Michael E. W. Varnum, Ph.D, an associate professor and social psychology area head at Arizona State University, who authored The Powerful Psychology of Cuteness last year, agrees. “Many of the entities we find cute – infants, puppies, Baby Yoda, or Wall-E – have features in common, like large eyes and stubby limbs. These are features that [Austrian ethologist] Konrad Lorenz dubbed ‘kindenschema’,” he says. “Encountering these cues, several things happen to our psychology: circuitry in our brain, active in experiences of reward or pleasure, tend to respond. We also feel a desire to protect the target with these attributes – part of an evolved parenting psychology. It’s not perfectly calibrated, and thus we might have similar feelings when encountering a little food delivery robot, or when cuddling our favourite teddy.”

Cuteness first came into its own in the West in the mid-19th century, says Catterall, explaining it was an early product of falling infant mortality rates. “Before that, no one really valued childhood,” she tells woo. It also coincided with the rise of mass production. “People realised if you put something out with a cute cat on it, people will buy it. So it’s very linked with capitalism in fact, and the idea of childhood changing.” If you look at the term’s etymology, it originates from the Latin word acutus, meaning cunning. For a while, being cute meant to be cunning, the curator says. “Those ideas have sort of collided now, and the way cute works is precisely because it has all these opposite meanings – often it’s ugly and cute, old and young.”

Japan, meanwhile, is one of the foremost promoters of cute aesthetics. The Sanrio brand alone has given us over 400 playful characters, among them Gudetama in 2013 and most famously, Hello Kitty (celebrating her 50th anniversary this year, she has her own disco space at Somerset House). “The Japanese idea of cuteness is very much born from ancient beliefs and ideas valuing things that are small and pitiable,” explains Catterall. The emergence of kawaii culture in the early 20th century, by the ‘70s and ‘80 a powerful tool of consumerism geared toward young women, at the turn of the century had cross-contaminated with cute culture from the UK and US.

Undoubtedly most significant in the story of contemporary cuteness, however, is the arrival of the internet. The web, Catterall suggests, has allowed cuteness to be more nuanced, and “it’s pretty much because of the internet [that cute has taken over],” she says. “Cuteness allows for quite malign things to exist in a non-judgmental way, so online it’s taken to places where it feels naturally at home. If you’re slightly outside of the norm, you can find a safe space and community, which is incredibly empowering. And as the world becomes precarious, especially for younger generations, the internet is a place you can be yourself.”

For women and girls especially, the internet, for all its very real horrors, has been the birthplace of multiple cute-adjacent communities. Previously finding a home on Tumblr, more recently TikTok has become a vehicle for trends obviously aesthetic-led but also social (and cats, naturally). Cute things in turn, notes Noir, can aid our sense of safety, with attributes that mitigate the potential for concern. “The features we associate with cuteness mimic those of a baby, so encountering cute stimuli makes our brain recognise them as non-threatening, sparking pleasurable emotions,” she says. “This perception of harmlessness contributes to a sense of psychological safety, making us feel comfortable. For some, it can serve as a coping mechanism for dealing with difficult emotions.”

Cuteness, Catterall thinks, is ultimately about embracing the ‘other’. “Of course women in a patriarchal society are completely othered, and cuteness leans towards the feminine, but it also leans towards the queer, and the anti-normative generally,” she states. “It’s in that whole realm of the other that cuteness finds its true strength, and what was important for us was the idea that cuteness fills you up emotionally. It requires an effective response, reacting with you on a physical, emotional and psychological level.”

And as for cute’s future? “It’s really hard to know, it depends where the internet goes,” she says. While Varnum speculates that “it may be that cuteness perception and associated thoughts and feelings are fairly stable, given their likely evolved roots. On the other hand, it might be the case that we see shifts in how the term is used and whom/what it is applied to, given shifts in values and behavioural tendencies that have occurred in many societies in the past several decades. Something to test empirically!”

CUTE is on show at Somerset House, London between January 25 and April 14 2024