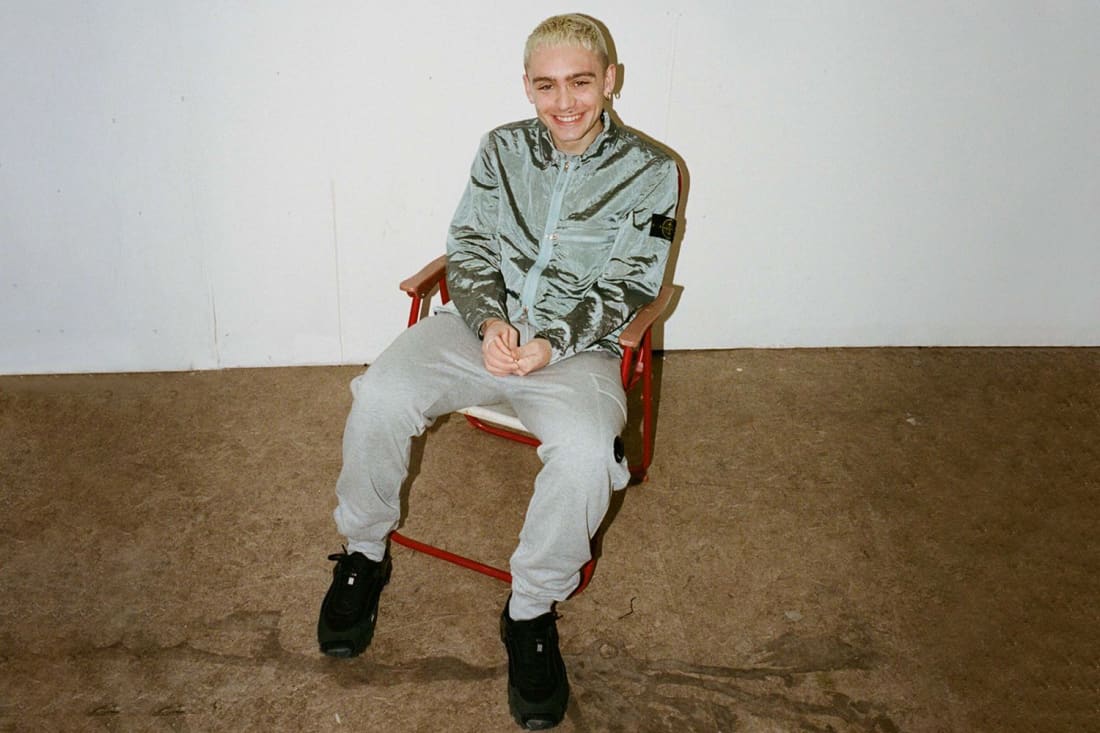

Performance art is magic, says Miles Greenberg

The New York-based artist examines the therapeutical function that his medium fulfils in his life for woo’s art column

The New York-based artist examines the therapeutical function that his medium fulfils in his life for woo’s art column

Welcome to Stop Scrolling, where each fortnight arts and culture writer Gilda Bruno will be bringing you a roundup of carefully curated exhibitions, art fairs and photo books to check out, as well as exclusive conversations with some of today's most exciting emerging artists.

This week, Bruno speaks with Canadian artist Miles Greenberg about the story behind his Water in a Heatwave performance - which has just been replicated at London’s Southbank Centre - and how being on stage allows him to reach a state of physical, emotional and psychological trance.

For Montreal-born, New York-based artist Miles Greenberg, there was never another alternative to art. “Art-making has never not been the centre of my universe,” he says. The son of Canadian television personality Michael Williams and trailblazing cultural visionary Phoebe Greenberg - an actress and film producer also active in the art scene who raised Miles herself - he recalls sitting on a tour bus with his mother and her theatre troupe as one of his earliest memories. “It all started with my mum,” Greenberg says. As a child, he would be handing out flyers at the Edinburgh Fringe, or “spending time with the clowns, the freaks and the weirdos”, Greenberg laughs. “People tend to get into art through a particular route,” he adds. “Instead, I went to every single Venice Biennale there has been in my lifetime, including in utero.”

Thanks to his early appreciation of art and its manifold disciplines, from a very young age, Greenberg began to treasure his “on-the-field” education over the lessons taught as part of the traditional school curriculum. “Because of our diverging experiences, there was a bit of a disconnect between me and the other students,” he says. Hungry to start searching for his artistic voice in the “real world”, Greenberg dropped out of school at 17, instead exploring his practice in “DIY spaces” including artist squats, cabarets, drag bars and other underground events. In 2019, having been accepted into London’s Central Saint Martins, Greenberg declined his offer in the hope of getting into Cooper Union. “Between 17 and 21, I had already lived in Beijing and Paris, but my dream was moving to New York,” the 25-year-old explains. “I rented out a cheap hotel room around the corner of the school and went there the following morning with my portfolio.” After waiting for hours for it to be reviewed, he was rejected, but that didn’t stop him from proceeding along his path or making the city his new home.

Eventually he settled on performance art as his medium of choice. Since the earliest days of his career, Greenberg has boasted high-profile collaborations with the likes of Marina Abramović, Canadian choreographer Édouard Lock, and American director and artist Robert Wilson. He’s also done a year-long workshop at Paris’ École International de Théâtre Jacques Lecoq - where his mother had studied- training stays at Beijing’s Red Gate Residency, New York’s Watermill Center, and participated in Abramović’s Cleaning the House workshop in Greece. It is in the wake of that first encounter with the godmother of performance art that, around six years later, Greenberg was invited to be part of the Marina Abramović Institute (MAI)’s five-day-long takeover of London’s Southbank Centre, which closed on 8 October.

As one of the 11 interdisciplinary artists featured in the event - consisting of eight-hour individual daily performances by Carla Adra, Paul Setúbal, Carlos Martiel, Collective Absentia, Paula Garcia, Yiannis Pappas, Despina Zacharopoulou, Cassils, Sandra Johnston, Aleksandar Timotic and Greenberg himself - the Montreal-born creative revisited his 2021 piece Water in a Heatwave. Hosted on the stage of the venue’s Queen Elizabeth Hall, the performance saw eight performers join the artist in a sensory, choreographic investigation into the body. Placed in couples on four square, mirrored plinths so as to encircle Greenberg’s own light-reflecting, cubic podium, the protagonists of the piece brought to life a slow-motion, sweat-drenched fight that translated into a hypnotic, intimate physical experience. Fronting feminine and masculine Black figures of different shapes, shirtless and made “other” by translucent contact lenses - a trademark of the latest works by the artist - Water in a Heatwave appeared to hint at the body’s ability to absorb tension, trauma and the resulting suffering and transform it into poetry, balance and new, renovated life.

Serving as the centrepiece to the performance, which landed after his 2023 groundbreaking presentations at the Louvre (Etude Pour Sébastien), Pace Gallery (Fountain II) and Brooklyn’s Powerhouse Arts (Truth), Greenberg straddled the Christ, the Devil and the Angel archetypes. In his pupil-less, tentative movements, he looked, at once, powerless and fierce, malicious and pious, nearing death or only just coming alive. Embodying the limits and possibilities of the human form in its rawest, most instinctual connotation, Water in a Heatwave stands for the contrasts that define our experiences - the “scarcity” and “abundance” of life - and our inner desire to move past what is deemed impossible. To celebrate the success of the MAI takeover and learn more about its behind-the-scenes, we speak to Greenberg about the making of this piece, his “generative” vision of art, and how performance allows him to leave “something behind”.

Your work lies at the intersection of classic sculpture and performance art. How does the reciprocal influence of these two mediums manifest itself in your practice?

Miles Greenberg: Well, you have performers and you have performance artists, but then you also have sculptures and sculptors. People often call me a performer, which is a totally valid misnomer, but it is one that rubs me in the wrong way. Performance artist is probably the most appropriate way to refer to me, or just artist, as my craft entails much more than just performance. I learnt how to perform by looking at sculpture. Performance was something I could access through my body. Compared to other people, I lacked some practical and technical skills, which made my approach to art very intuitive: I would respond to whatever was around me. It could be a statue like The Winged Victory of Samothrace or the Cour Marly - my favourite room at the Louvre. It was always places like the Met or the Prado Museum, with their spectacular halls of marble, that inspired me the most. Three-dimensional objects and structures were where I felt the most vivid correspondence with my body and with the bodies of the spectators in space. Watching how the sculptures were staged in those spaces, how people reacted to them, what bodies they represented, and paying attention to the spatial and hierarchical relationships that existed between them is what taught me to do what I do now. It has been an interesting education that unfolded through seeing as opposed to academic learning.

Performance even allows you to give life to your own sculptures

Exactly! Most of my sculptures are created from 3D scans of my performances. The fact that my practice generates on itself - as one performance leads to a series of scans, video works or relics - is a reflection of my Gen-Z view of art, which looks at art-making from a generative perspective. I talked a lot about this during my recent Fountain II performance at Pace Gallery, where I was put in conversation with Hermann Nitsch, one of the founders of the Viennese Actionism movement. As a now-deceased, white man from Austria who grew up during WWII, his context of reference was radically different from the one I grew up in. Although we have both experienced a lot of violence, we articulate it in very different ways. And the way I feel compelled to do so as part of this specific moment in time is by producing pieces that evoke a sense of abundance rather than a sense of scarcity in the viewers - pieces that refuse to contribute to further violence in the world. I find myself thinking a lot about my footprint as an artist and what I will leave behind and, while I still don’t know what this will be, I know that there is a closer tie between ancient Greek and Roman statuary, my generation’s sensibility and that of other recent contemporary artists - we aim to leave a tangible mark.

Some might look at performance as a means of “exiting” the body but, for you, the opposite seems true: you use it as an opportunity to dig deeper into your physical, sensorial and emotional dimensions. What intentions guide your performances?

Although some of my performances might involve pain, it is definitely not the focus - nor the end - of my work per se. Even when the conversation revolves around violence, the performance is never just about suffering. For me, pain is a tool to get to a certain mental state or paint a more vivid picture of a given situation. We have finally reached a place in contemporary art where we can look at work by Black and queer artists without having to limit ourselves to narratives of oppression and subjugation. We no longer have to look at their work and the pain that might well be captured in it as the crux of what they or better, we, are ultimately saying. Today seeing Black bodies in art goes far beyond slavery, and I say it for a reason: every time I do a show, somebody makes a comment about it, which I find reductive, as if every single gesture enacted by a Black body was still enraptured in this history. I grew up looking at the classical European canon of art as a reference point for my understanding of love, the universe and the entire gamut of human emotion - not just pain, not just suffering, but of course, those too. If as a Black person, I was always able to make the translation between a Greco-Roman body, a Rococo body, a Renaissance body and my own figure, it shouldn’t be such a radical ask for the audience to do the same with the bodies in my performances as they speak of something universal.

How do you prepare ahead of a performance?

I am always on a strict diet, I follow a strict regimen of stretching exercises and, over the years, I have developed my own methods. I don’t necessarily impose those on my performers if I am in a group, but I do give everyone some movement preparation with a focus on fostering their sensibility around the movement language - which is the vocabulary we work with. When working traditionally, I think it is important never to think about time, and to go into the void of just presence - you have to be a body more than a mind.

How would you describe the state you reach during your pieces?

My work is just as much about dissociating as it is about being hyper-present. It is an open invitation to myself and my performers to meet exactly where we are. For me, it is the most effective form of therapy, and I have tried many. It is a status-sizing sort of scenario in which my body can manifest itself and respond as it is. Opening that invitation to other performers and seeing other bodies interact in that same space is an experience that can’t be put into words. While the movements setting the pace for each performance and its visual aesthetic are decided upfront, I try not to dictate the mental state of performers appearing in a given piece. I can give them advice on how to survive a performance, but it is up to them how to be part of it. After performing for eight hours, there isn’t a single dishonest bone in your body. And if being hyper-present, stoic and all of these things isn’t where you are at, you are not going to be that after eight hours. Instead, you are going to be floating in the air, distracted, sharp, angry, ecstatic or euphoric - you are basically going to be whatever you are. You go into a trance and what comes out of it is something very poetic, honest and magic… that is the secret inside of performance. My work is very much an embodiment of my mental state - I have OCD and this is how it manifests. The least anxious, the least symptomatic I am, is when I am on stage.

You were one of the protagonists of the Marina Abramović Institute Takeover (4-8 October). How did you become involved in this project?

Marina is like my second mum in a way - we have been friends since I was a teenager. She has always been very generous to me and I see her as a strong mentor. Although our work is completely different, she laid the bricks that we stand on in trying to make performance a mainstream medium. I still remember seeing The Artist is Present when I was 12, the piece taught me what performance art was - it totally revolutionised how I thought about creative work in general. The work I presented within the Southbank Centre showcase is called Water in a Heatwave. It was created two years ago, in October 2021, and unveiled for the first time in Portugal, but I revised it slightly to adapt it to the stage of the Queen Elizabeth Hall. The performance is based on the idea of wrestling and has a lot of tension within it, which the audience is called to engage with. Although there isn’t any direct contact between viewers and the performers, as the public is only allowed to be part of the work in a passive, observational way, Water in a Heatwave immerses those witnessing it in a space that exists outside of time and space. It is an ode to my Black universe, love and everything in between.

What would you like your legacy to be?

A lot of artists are interested in the ephemeral, but I am not one of them. I am constantly thinking about posterity. Even my props are made to last - they are carved out of precious and semi-precious metals like silver. I want them to be archaeological one day. There are those who claim that all of this will be dust, which is true, but if there is anything that I want to leave is giving licence to the general public to experience themselves better, to heighten people’s sensitivities, to leave memories, objects and documents behind - human shrapnel - that reminds people of themselves, their bodies and the world. Nowadays, it is getting easier and easier to forget about the world: what I am trying to do is keep people’s eyes on what is in front of them and who they are.

EXPERIMENTA, immersive art and extended reality works programme, BFI, London, UK, through 22 October

On the occasion of the 67th BFI London Film Festival (LFF, 4-15 October), the British Film Institute has just launched a new, cutting-edge programme showcasing the work of international film artists with a focus on experimental moving image pieces. Titled EXPERIMENTA and continuing through 22 October, the initiative was born of the desire to provide viewers with the opportunity to “experience powerful ways of storytelling that revolutionise and reshape our vision of cinema”. Informed by the social, political and cultural challenges that define our era, from world conflicts and the lasting legacy of colonisation to issues of representation, climate change and more; the programme brings together some of the most exciting names on the global film scene, including indigenous artist filmmakers from the USA, Australia, Canada and Siberia.

Nicole Eisenman, What Happened, solo exhibition, Whitechapel Gallery, London, UK, through 14 January, 2024

Verdun-born artist Nicole Eisenman’s practice is brought into focus in What Happened, the first major retrospective of her work in the UK, which is open at London’s Whitechapel Gallery through 14 January. Gathering more than 100 artworks developed over the last 30 years, including pieces never-before shown in the country, the showcase is a testament to Eisenman’s effortless inventiveness across painting, drawing, animation, sculpture and prints. Curated into eight thematic sections, What Happened invites the audience to embrace the artist’s humorous rendition of everyday life to unveil how, through humour, Eisenman subtly taps into some of today’s pressing issues, from “gender, identity and sexual politics, recent civic and governmental turmoil in the United States, protest and activism, and the impact of technology on personal relationships and romantic lives”.

Tomorrow, Today, Yesterday, group exhibition, Modern Forms, London, UK, through 26 November

Inaugurated as part of London’s Frieze Week, Tomorrow, Today, Yesterday breathes new life into the centuries-spanning medium of sculpture by fronting the creations of some of London’s most thought-provoking, young contemporary sculptors, including Amba Sayal-Bennett, Billy Fraser, [pɑːtɪk(ə)l], Jesse Pollock, Florence Sweeney and Grace Woodcock. Hosted within the monumental, Grade II listed building that is Modern Forms’ Floreat House in Mayfair, the group exhibition looks at art as a bridge between past, present and future by sparking reflection of the function that artefacts acquire in times of crisis. Accompanied by a series of texts on the featured artists and the showcase itself by writer and curator Bella Bonner-Evans, Tomorrow, Today, Yesterday examines the diverging approaches to sculpture embodied by the work of a new generation of practitioners. From modular structures and 3D-printed pieces to metallic dystopias, emotionally charged textures, abstract silhouettes and resined creatures, the exhibition captures the breadth of their experimentation while celebrating art as an agent of change, as a portal into new dimensions.

RE/SISTERS, group show, Barbican, London, through 14 January, 2024

Launched at London’s Barbican Centre on 5 October, RE/SISTERS is a new group showcase unveiling the connection between gender and ecology through the film and photography works of 50 emerging and established women and gender-nonconforming artists. Taking the systemic relationship between “the oppression of women and the degradation of the planet” as its core, the exhibition attempts to demonstrate how “women’s understanding of our environment often resisted the logic of capitalist economies which places the exploitation of the planet at its centre”. Featuring artworks by leading female artists of the likes of Judy Chicago, Gauri Gill, Barbara Kruger and Francesca Woodman, RE/SISTERS captures women creatives’ relentless activism in support of the environmental stance and their unique contributions to the artistic landscape of the 21st and 20th-century.

DaddyBears, Shiny Sexy Soft, solo exhibition, Roman Road, London, UK, through 1 November

Open at London’s Roman Road until 1 November, DaddyBears’ newest solo show, Shiny Sexy Soft, the first one developed in collaboration with the gallery, is an honest look into the world of sex work. Reinterpreting the glamorisation and stigmatisation that traditionally alternate in defining people’s understanding of this secluded universe, the London-based artist unleashes a “broken fantasy” that voluntarily clashes with viewers’ collective imagination. Hosted within a scarcely lit space with pitch-black flooring, Shiny Sexy Soft presents a new selection of soft sculptural works juxtaposed to expansive, floor-to-ceiling textile photographs depicting a home interior covered in lo-fi stock images of female nudes. Channelling DaddyBears’ own imagination, the exhibition strives to “reappropriate one man’s interior design choices into a new and fantastical room of her own”.