Striking images interrogating the relationship between photography and identity

In his first ever solo project, photographer Oliver Frank Chanarin investigates what it means to capture identity in post-modern Britain

In his first ever solo project, photographer Oliver Frank Chanarin investigates what it means to capture identity in post-modern Britain

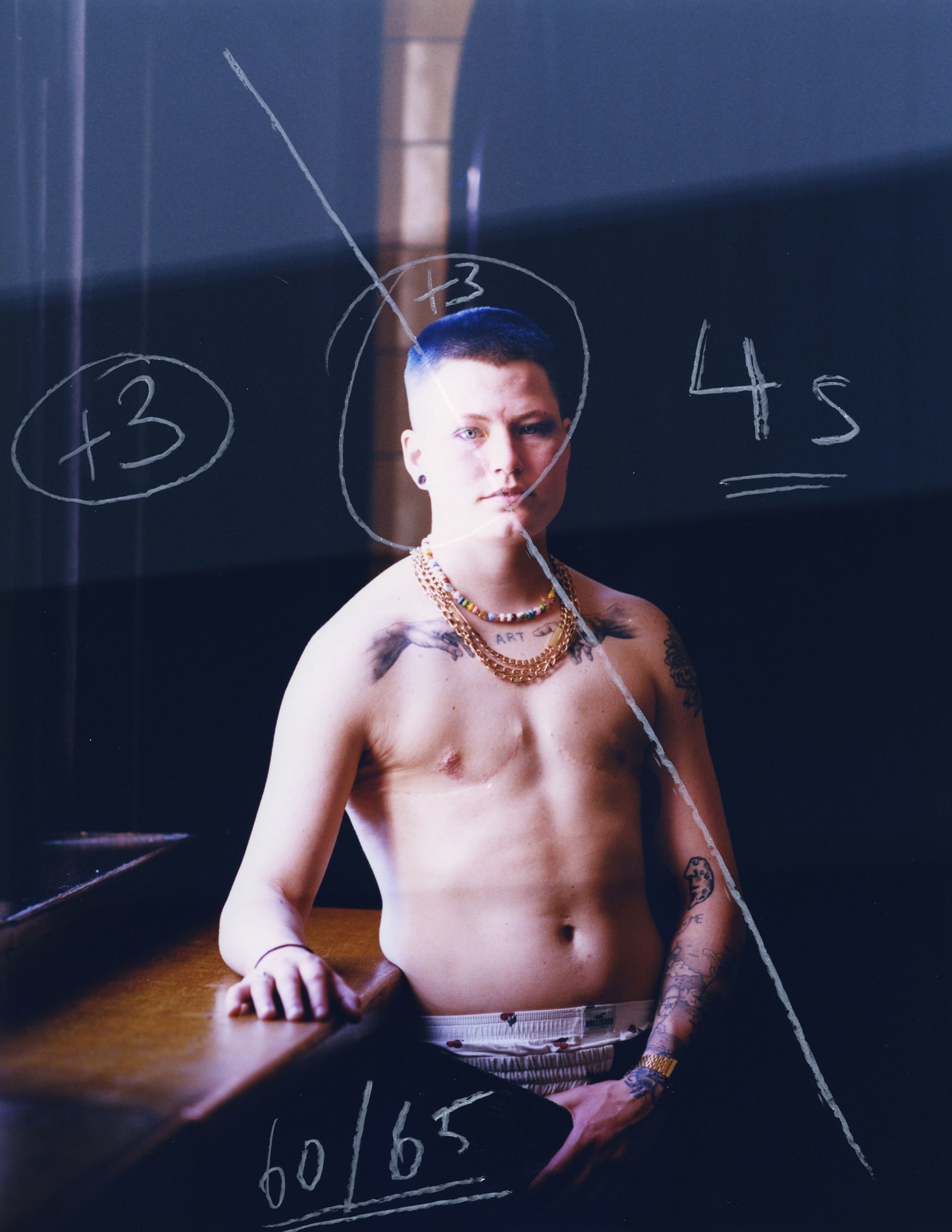

Young British Army recruits; adults in drag, fetish enthusiasts, suspicious-looking teenage girls – these are just some of the people you encounter upon opening Oliver Frank Chanarin’s first solo photo-book, A Perfect Sentence. The collection, composed of mostly portraits, visualises identities living in the fringes of contemporary Britain. The result is a body of work that attempts to reimagine what identity looks like – and indeed how it is to be perceived – in a post-Covid culture.

Chanarin, actually never intended on pursuing his now-prolific photography career: “When I first started, I was editing a magazine called Colors – this extraordinary magazine about culture all over the world. It was [published] at a time where the idea that somebody growing up in South London could eat sushi was radical,” he remembers. It was there that his fascination with discovering and lensing different identities found its feet.

At first glance, A Perfect Sentence appears as an expedition; a pursuit to find and photograph people on the margins of society and to bring their existence into the light. But Chanarin’s first solo venture evolved over time into something far more troubling. For him, the work poses pertinent questions about the power dynamics within documentary photography and the lines between reality and art.

“I take the negative and I go into a darkroom and I start to print. But when I print, the colours change and the shadows change – the picture takes on a different quality. Eventually, the authorship of the person in front of the camera becomes weakened a bit,” Chanarin argues. “As much as I want the experience to be consensual and fun and empowering, the picture, ultimately, is part of a work of art done by me.”

And it is this tension that typifies the photographic narrative of A Perfect Sentence. In his new photo book, Chanarin meticulously explores the nature of identity and self-representation, the ethics of documentary photography and the intricacy of obtaining consent from photographic subjects.

woo sat down with the image-maker to find out more about the evolution of his first ever solo-project, transitioning from a partnership to creative independence and what the experience has taught him about the nature – and future – of his craft.

This is your first solo project - how has this felt for you as an artist? Freeing? Daunting?

Chanarin: I worked in a partnership with the photographer Adam Broomberg for 20-odd years, which began at the beginning of my career. So I'd never done anything on my own as an artist – as a photographer. And truthfully, I was terrified. I just felt this urge to go back to the origins of why I started photography, which was this simple pleasure of being in places that are not familiar to me; being out in the world and having to think on my feet, and having experiences with people that I wouldn't ordinarily meet. So I wanted to come back and revisit this experience of simply making pictures again.

Tell me about the creative process behind building your first body of independent work

Chanarin: The idea of the project was to step out of my own kind of echo chambers - my own little bubble of where I live - and go have encounters with strangers and seeing what I found. I was inspired by the work of August Sander, a German photographer from the 1920s, who famously documented German society and wanted to show everything was connected by documenting what he called archetypes [of people]. But pretty quickly that as a reference didn't feel helpful anymore. This idea of identity that we have today is so much more complex and layered and multifaceted than it was back in 1920. It just didn't make sense to try and say that somebody was one thing; a bricklayer can also be a father and they can also be a BDSM participant. So what started as this attempt to make a kind of survey of Britain post-Brexit and post-Covid, ended up being some being much more subjective and personal and actually not about Britain at all. But more about the act of photographing.

When did you first start to reconsider the role of consent in your photography?

Chanarin: I had an experience right at the beginning [of the project]: I was working with different museums in different parts of the country. The first was in Liverpool. And while I was there, my partner museum asked me to teach a workshop to a group of young people in an art centre. So I did this photography workshop making black and white paper negatives with them and everyone loved it; people took photographs of the work with their phones, and the whole thing went really well. But then that night afterwards, I made the error of posting on my Instagram account one of these black and white pictures [without consent of all participants]. The museum told me that I had broken their safeguarding policies and cancelled my exhibition.

I found the language of these safeguarding policies really interesting and pertinent in terms of this relationship between photography and subject. And that became a kind of manifesto for how A Perfect Sentence was made. Good things come from bad things, really, because it was a bad experience but it actually framed the whole project in the end.

How did the project help you to think about photographic consent differently?

Chanarin: When I first started developing a craft as a photographer, I had quite extraordinary access and I was using the camera as an opportunity to get into places that I would never, ordinarily, manage to enter. It was an incredible experience, but after a few years of doing that kind of work as a documentarian, I started to become quite suspicious of what my role was. Very often, I was photographing people that were quite vulnerable – sometimes in a lot of pain. So my role with a camera felt sort of uncomfortable and I wasn't quite sure what I was doing there – was I a journalist? An artist? I started really thinking about what it means to be a witness and to wield the power of holding a camera.

How important is it to give subjects a level of agency in their photographic representation?

Chanarin: When I first started making photographs, only 100 people would see them. Now with the internet, there's so much more at stake, and there's so much more visibility. And with that has come a lot more anxiety. And being a white middle-aged man, I was very aware of what I represented; the ways in which I could be a trigger. It didn't feel comfortable and safe for the people I was photographing to have me kind of barge in and encounter people in a natural way. So, while some of the pictures in the book are taken through these very chance encounters, most of them are made through a series of engagements with communities and organisations and a huge amount of correspondence [leading] up to the point of taking the picture.

A Perfect Sentence by Oliver Frank Chanarin is published by Loose Joints. An exhibition of the work produced by Forma is on show at the Museum of Making, Derby, until 3 September 2023.