why is jeremy allen white’s calvin klein ad acceptable but fka twigs’ isn’t?

The singer’s advert was banned by the Advertising Standards Agency, leading to accusations of hypocrisy

The singer’s advert was banned by the Advertising Standards Agency, leading to accusations of hypocrisy

The curvature of a bum cheek and peek of side boob caused quite the stir last week. fka Twigs’ Calvin Klein ad was banned by the Advertising Standards Agency in the UK after a grand total of two people complained that the image of the singer was inappropriately sexual. The regulatory body agreed, due to the image centring more on fka Twigs’ “physical features” than the “clothing”. This, they said, amounted to her being presented as a “stereotypical sexual object” that could cause “harm and offence” to children.

But will seeing fka Twigs’ bum really cause anyone harm? First off, social media is now much more sanitised than it was in its infancy, due to increased regulation, policy teams and frequent moderation of what people should or shouldn’t see. While Tumblr was a sexual wild wild west with Topless Tuesdays, porn gifs, and sexual content geared towards teen users, TikTok now forces people to self-censor words including sex (which has become “seggs”). Bodyform claimed women’s health words were being censored in their posts, including “labia majora”, “vagina” and “vulva”.

For millennial feminists who pushed for less shame around sex and proudly displaying different body types, normalising sexuality is a tool for liberation. Campaigns such as #freethenipple fought against the erasure of women’s bodies online, believing that displaying men’s nipples proudly while forcing women to cover theirs (even in non-sexual contexts like medical or breastfeeding imagery) leads to society seeing a woman’s nude form as inherently sexual.

Platforms such as Instagram are currently guided by the same rules as the ASA that notably seem far more concerned about the sexualisation of women over men. Meta’s advisory board, which influences Facebook and Instagram, is made up of academics, politicians and journalists who have recommended that their adult nudity and sexual imagery standards “respect international human rights standards” across genders.

In response to the advert being banned, 36-year-old Twigs posted: “I see a beautiful strong woman of colour whose incredible body has overcome more pain than you can imagine. I am proud of my physicality and hold the art I create with my vessel to the standards of women like Josephine Baker, Eartha Kitt and Grace Jones, who broke down barriers of what it looks like to be empowered and harness a unique embodied sensuality.”

It’s notable that she points to Black women in this post. That may be because over recent years there have been fears that shadow banning and algorithmic bias hides certain communities from view. Salty, a feminist sex and relationships magazine based in the US, published an article that said: “There are rumours, talks, conversations happening in our communities about how certain bodies and perspectives are being policed, and how certain people are targeted for censorship more than others on Instagram.” After teaming up with the University of Michigan, they proved this theory and found that queer users, and women of colour were policed at a higher rate online. Meanwhile, plus-sized influencers' posts were found to be more likely to be flagged for “sexual solicitation” and “excessive nudity”. All this, they argue, could have a knock-on effect for whose body is deemed acceptable for public viewing.

Karen Middleton, senior lecturer in marketing and gendered advertising expert, tells woo that Twigs’ ad may have been taken down due to how “unattainable” the musician’s physique may seem for a lot of people. “It’s well-defined, it’s muscular, it’s a very attractive aesthetic as well as being revealing but physical perfection puts a lot of pressure on women,” she says.

Middleton says it’s well-documented that the psychological impact of promoting certain body types changes the way young women and girls feel about themselves. Researchers have repeatedly found that seeing “very thin bodies” in media and advertising is connected to women feeling “dissatisfied with their bodies wanting to be very thin, and it influences their eating behaviours”. The ASA changed its rules in 2018 after the Committee of Advertising Practice ruled to combat damaging gendered advertising.

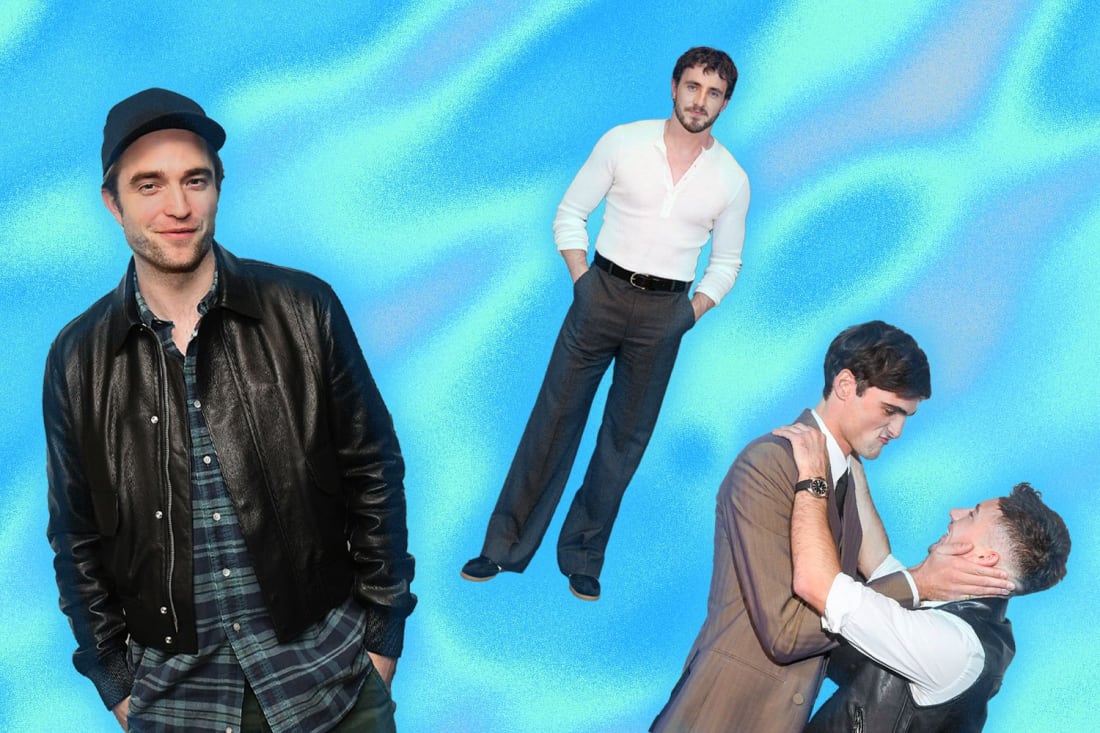

Why, then, was there approval for Jeremy Allen White’s Calvin Klein ad? In it, the actor appears fully-clothed in a vest and trousers before stripping down to his underwear and doing a pull-up. “[The ASA] aims to be fair across the sexes,” says Oliver Bray, a commercial lawyer at RPC. He watches their rulings quite closely and suggests that fka Twigs’ ad could be seen as damaging because “there’s more body than shirt”, meaning it’s overtly trying to titillate viewers who may not even notice what the product is. “It’s like trying to sell toothpaste with a pair of women’s legs,” he says, referencing a banned advert from 2017.

Bray adds that “the bigger context at play here is trying to stop children from ingesting overly sexual content just because it’s cool,” noting that these billboards would be displayed where people of any age could see them. Some studies have found that girls who are exposed to sexualised images from childhood are likely to use condoms less, have less sexual assertiveness and an increased sense of shame associated with sex. Boys who are exposed to sexualised images from a young age, it’s been found, can show signs of increased sexual aggression.

So, what fka Twigs sees as a double standard might simply come down to the product Calvin Klein was trying to sell. “The ASA are trying to say stop focusing on parts of the body you don’t need to just because the photographer feels that will be more eye-catching,” says Bray. “Jeremy’s body is on display because he’s selling underwear. They can get away with it because you have to show the body to show that item.”

For years, women have been hypersexualised to sell things like yoghurt, sometimes as just a set of limbs, in contrast to the powerful, Adonis-like way men are often portrayed. Middleton argues that the varied reactions to each campaign could be us wrestling with changing times. “It’s almost like within a patriarchy, [objectifying men] is seen as progressive,” she explains. Yet men aren’t immune to beauty ideals, with the rise of ‘bigorexia’, the obsession with gaining giant muscles and looking hench, mostly impacting young men who buy workout-aiding substances online. “We do need to look at this through a feminist lens and in a wider context, in terms of thinking about the double standard,” she says.

Sex-positive feminism has taken a bit of a battering in recent years. Gen Z are seemingly not as convinced by the repeated exposure to sexuality being a net good for women, with some feeling it largely benefits men. Young people are, according to some studies, more averse to sex scenes on TV as well as having casual sex. Several pieces of research reveal today’s teenagers are having less sex, leading to millennials labelling them as a prudish generation.

Some women artists feel personally empowered by baring all, freeing themselves from shame and learning not to hide their bodies – and that’s great. In that way, some might see it as sexist that Twigs’ autonomy has been robbed by this ruling. “It’s not a straight answer,” Middleton explains, though she continues with another counter-narrative. Unfortunately, science doesn’t fully support Twigs’ idea that objectification’s harms lessen when a subject is portrayed as in control.

“In the past, women [in the media] were often portrayed as passive and focused on their appearance, but now there's a change where women are shown as powerful,” Middleton says. “One study showed passive or powerful types of images, compared to neutral ones. Both made women more dissatisfied with their weight. The powerful portrayals, in particular, made women feel more like objects and may still lead to things like disordered eating.”

As new rules emerge about how women’s bodies can be shown without inadvertently reinforcing century-long problems of how they’re represented in media and what women have been made to feel they should look like, it seems fka Twigs has fallen victim to a ruling that clumsily grapples with two opposing movements in feminism. Is the image any worse than what we’ve seen before? Certainly not. But has what we’ve already seen damaged our brains inadvertently? Possibly.

Latest