The Traitors: this is why we love to watch deception

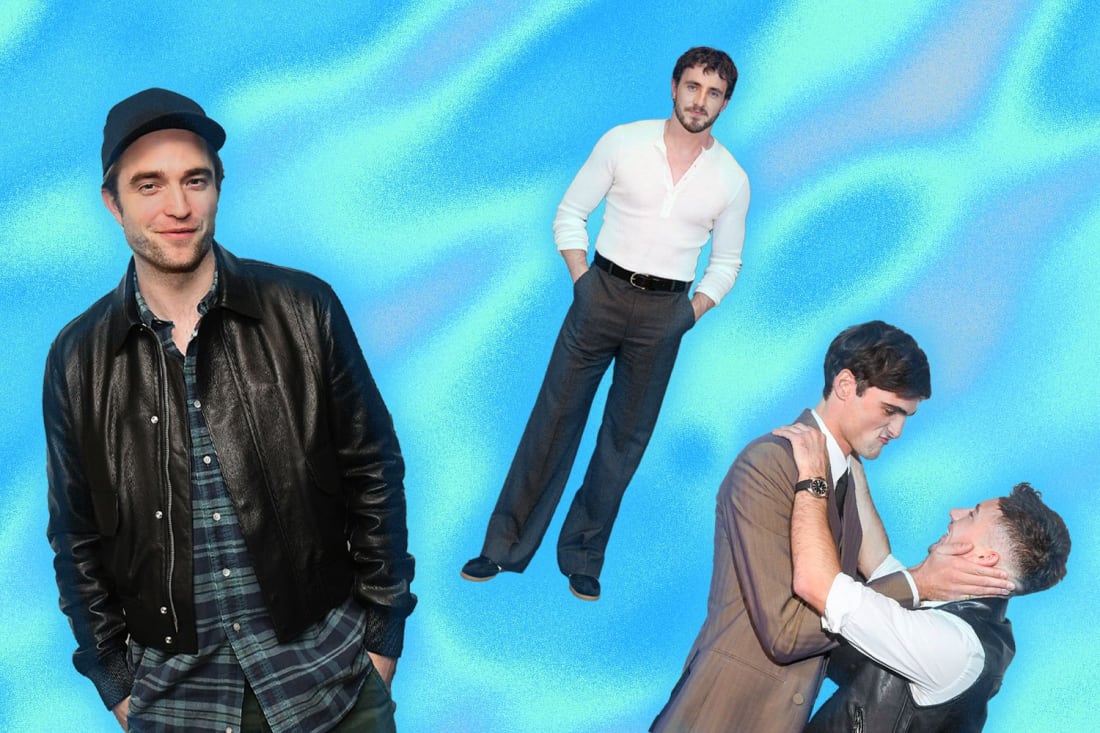

Psychologists, lying experts and contestants Paul and Wilf tell us more about the art of deceit on the TV show

Psychologists, lying experts and contestants Paul and Wilf tell us more about the art of deceit on the TV show

Castle fever has hit the UK: we’re all obsessed with The Traitors. As one cliche from the show goes, we’re just going by the facts here. Like the fact that social media is now one big Diane stan account. Or the fact that any of us in relationships questioned our own faithfulness after Ross’ camera wink. And the numbers don’t lie – the show reached 4.4 million viewers last week for a single episode. With the final three episodes around the corner, it’s still all to play for.

In case you’ve been banished to a dungeon with no signal and somehow missed out on all of this, The Traitors is a BBC game show which sees 22 strangers living in a castle compete for up to £120,000, building up the prize pot through Raven-for-adults challenges (giant outdoor puzzles and catapulting stuff at other stuff).

But while the vast majority of the group are told they will be playing as “faithfuls”, a handful are selected to be “traitors” and can “murder” each night. The task of the faithful is, through round table discussions, to evict the traitors and bag the cash. It’s one of the diciest, most deceitful games TV has ever seen.

But why are we so into it? Obviously, we’re mad for the drama of it all, from Claudia Winkleman’s capacious turtlenecks to a soundtrack that’s basically Florence if her Machine got corrupted by AI. Really, though, it boils down to one thing: the lies. We love them. The slimier, the snakier – hell, the smilier – all the better. But why?

The pleasure of deceit

Lying is part of human nature. Most people lie once or twice a day, with the most deceitful one per cent of us serving up around 15 whoppers a day. It’s part of our wiring. “It's no surprise The Traitors is successful: it taps into something that is fundamental to who we are,” Ian Leslie, author of Born Liars, tells woo.

Because humans lived in larger groups than other primates, “we needed to develop more sophisticated social skills, so we developed the ability to detect deceit at the same time as we learned to deceive others in our group,” he says. It even possibly made us more clever. “Indeed, some evolutionary biologists argue that the need to deceive and detect deception was the driving force of our exceptionally high intelligence,” he says, adding that we grew bigger brains to cope with this new, untrustworthy world.

And while lying might no longer be evolutionarily advantageous, it can help us in social situations, our very own Traitors shield to prevent us from getting banished from the group. After all, deceiving others can help us get what we desire more quickly than going down the honest route. White lies, too, can soften the blows for others. Truth is, most of us at least sometimes really enjoy it.

“It's dopamine, pure dopamine,” says Paul Gorton, one of this series’ most devilish, diabolical Traitors, who was ousted by another, Harry, in a genuine act of betrayal. His villainous performance inspired countless memes, including him being labelled “evil Van Gogh”. “It's getting away with murder. The next thing your human brain wants to do is say, well how can I do a little bit more and still get away with it? How do I just keep going until I get caught? That part was absolutely thrilling,” he adds.

It’s this fact that we can get away with it (at least sometimes) that makes it worth it. “Most people make for convincing liars. We lie because we understand that there is a reasonable chance of it being successful,” Dr. Chris Street, Senior Lecturer in Cognitive Psychology at Keele University and a lie detection expert, says. “If our lies were unlikely to be successful, we would likely choose not to lie.” When it gets us out of stressful situations, or avoids unpleasant emotions, it feels all the sweeter.

Of course, the only lying we’re doing while watching The Traitors is horizontal, and on the sofa. But TV is vicarious – we live through the characters and events unfolding in front of us and, in a small way, experience their emotions. We wonder, then, about what we could get away with. “How many times have you been in the office, or in a queue, and wanted to lie?” Paul says with a cackle. Er, no comment.

Getting away with it

We haven’t, obviously, all turned into Paul overnight, hosting secret meetings in the toilets with our colleagues to work out how to banish our boss. We might all tell the odd fib, but not all of us have the traits of a true traitor. As the show has shown, some of us are a lot better at lying than others.

“Being a good lie-teller typically depends on how you come across to others. Some people don't seem to raise suspicion,” says Aldert Vrij, Professor of Psychology at the University of Portsmouth and a world leader in detecting deceit. “This could be related to personality. Extroverts and expressive people are more likely to be believed than introverts and socially anxious people,” he adds.

The real trick for a traitor is getting the balance between lying well and lying low, apparently. “The traitors should not stick their neck out. Ash was very poor. She was far too keen to find out who the others thought was a traitor,” Vrij says. “When Paul attacked Miles, a fellow traitor, at the round table, he also went too far. He even said that the others should send him home if Miles turned out to be a faithful, which was expressing confidence at a very high level that probably only traitors do.”

This also applies to the faithful. “For verbal lie detection to work effectively, someone needs to encourage the target person to talk. But this is difficult in The Traitors because you run the risk of [making yourself a target] if talking to a traitor.” Basically, be quiet, but not too quiet, because that’s shifty too. “I think myself and Harry, and people like Ross, Jasmine, Kira, Diane, these people managed to just keep their cool and keep within it, whereas others, they lost their mind. It's very The Belko Experiment type stuff,” Paul says.

What makes it tricky for the innocent ones, though, is that we’re even worse at working out who is lying. “People are poorer lie detectors than they think they are. During off-screen conversations they probably start to think they know each other and could detect their lies but this is wrong,” Vrij says. According to his research, too, traditional tells — like averting your gaze — actually tell us nothing at all.

“I personally think social skills and personality play a big part in the traitors abilities to lie,” says Wilf Webster, who competed in season one of the UK series. “If you can make strong bonds with people quickly, they find it harder to believe you could be a traitor – and that is the name of the game.”

For now, Harry is practically engineering the entire game, avoiding any accusations of deceit even though he is straight-up lying to everyone’s faithful faces. Part of it is also down to self-deception and truly believing you are faithful. “Me and Harry were so dedicated to being faithful that if we spotted traitor-related behaviour we had to call it out in order to maintain our position in the group,” Paul says.

From our own (pillow) forts, most of us seem to be rooting for Harry too. So why do we want some liars to get caught and others to get away with it? “I think it's down to the character and the charisma,” suggests Paul. “Say if you watch the Joker and Joaquin Phoenix, you start wanting him to win. But some villains aren't likeable characters,” he adds, comparing himself to Jafar from Aladdin. “I think people saw me do bad things and thought, you’re so naughty, carry on. The UK public got to a position where people started to love to hate.”

Wilf tells woo that “people disliked watching Paul at times because he was able to separate the emotion from the role. He fully embraced the villain role and viewers sometimes get so immersed they forget it’s a game. Harry seems to have more empathy and guilt, which makes it easier for an audience to warm to him.”

It’s all fun and games

Of course, we don’t all love to lie and we don’t actually hate Paul. It’s a game, after all. While low-stakes lies or trickery during gameplay, as in The Traitors, can be a rush, being dishonest in real life isn’t always half as fun.

Getting away with it might be quite the thrill, but lying also activates the limbic system in the brain, leading to the kind of stress you could really do without. Also, the whole point about it causing other people a whole lot of hurt. Plus, getting caught isn’t a laugh – deceit can never overwrite receipts. So don’t lie too much, yeah?

Instead, take pleasure in the most perfect presentation of artful artifice ever beamed onto our screens. “It’s a game scenario. It’s like when watching a film, as humans, we can enjoy witnessing people getting battered because we know it's a film, so we take a little pleasure in it,” Paul says. “The Traitors has given us a guilty pleasure. And villains.”

For Paul, getting to play a traitor was a true treat. “I've just been put in a place where they've gone, ‘Paul, the rules of society are different for you. Your rules are you have to lie. You have to manipulate and you have to deceive’,” he explains.

Remembering it’s not real, though, is easier said than done – especially if you’re playing. “You totally lose yourself, like you fall in love with people in that show, and they become your family. You lose any type of realisation that the world exists outside of the castle,” he says. Wait, it doesn’t… does it? Please say you’re lying…

Latest